The Big Interview: Ashleigh Goddard

After suffering a concussion injury, Ashleigh Goddard went from what was likely a routine operation to suffering a stroke. Six months later, she was back on the football pitch doing what she loved...

“I’m good,” says Ashleigh Goddard, with the twinkle of a smile. “I still have annual scans; I’ve got one in May and then another next year to decide if I need more treatment or not. I go about life as normal as I can and just try to get on with things.”

If you are a regular follower of the women’s game, you may already know Ash’s story, but whether you or you don’t, the details are still worth listening to, the details of journey to recovery as stark as they are resiliently impressive.

“After everything, I didn’t know if I’d even be able to use a knife and fork again. It was a huge amount of work, but it was luck my body responded the way it did.

“I try to do loads of things that are expected of me, but I wanted to push myself. I’ve learned how to snowboard, come back to football, won a league with AFC Wimbledon. I’m all about pushing a little bit, and I’m grateful it’s going well so far.”

If you don’t know the story, Goddard tells it with a vividly picture-perfect recollection of events, and while she herself laughs at how “long-winded” the story itself is, it feels remiss to interrupt her recollection in such detail.

So, if you’re unaware, this is Ash Goddard’s story.

This is a free to read post, an example of the in-depth storytelling which comes with a paid subscription.

Check out over 100 more unique stories in WFC’s Premium section, available for just £45 for 12 months, paid in one go, or a £6 a month rolling subscription.

All subscriptions come with a 7-day free trial to allow you to explore our full archive.

Plus, guarantee you everything that is to come over the next 12 months…

“At the time, I was playing for Crystal Palace,” she begins. “I had just come off the back of a really positive season where I’d been captain and top scorer. We were playing against London City Lionesses and one of their girls came through the back of me, I got hit awkwardly and hit my head.

“The physio, Lyla, wouldn’t let me play again until I had scans. We’d done the concussion protocols, but I was a little bit up and down. I had fuzzy vision, so I went for a scan, and it took quite a while to get the result. There was nothing from that result, but we found something else.

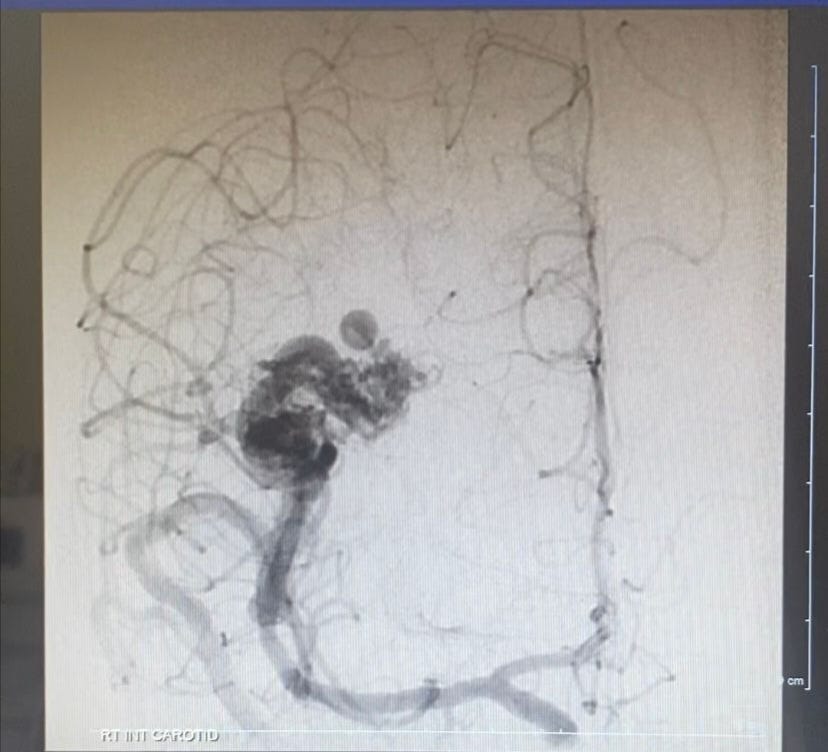

I had an AVM [Arteriovenous Malformation], which is a tangle of blood vessels in the brain where there shouldn’t be. Things just escalated from there, I had a further scan, went through a GP to UCLH [University College London Hospitals] who took this case on, and they found an aneurysm.

“The first thing you do is Google it - exactly what you shouldn’t do! It was seen as rare, but not that rare, not the end of the world, then you look into it more and more people don’t even know they have them. I kind of expected that to be it, I’d turn up and they’d say they’d monitor it, but I went into an appointment, and I was told I had an aneurysm and there was only one course of treatment. They couldn’t go in and take it out because it was too deep, it would have killed me.

“They basically told me I had a timebomb in my head, so I needed an embolization, which had a 90-95% success rate, this was all during COVID-19 as well. I went in thinking I’d be out the next day, but I fell into the 5-10% and had a stroke. I woke up in the high dependency unit, paralysed on my left side.

“At that point, I was so high on all the drugs it was all a blur, I didn’t put two and two together. I look back and think, ‘how did I not realise I’d had a stroke?!’ But when they told me it was like a big surprise to me! I was in hospital for a week, it was COVID-19, so nobody could visit which was really hard for my family.

“It’s hard for them to hear, but it almost helped me, or at least benefited me. I knew it was bad, but by not seeing them and how they felt sheltered them a little bit from how bad it was. There was nothing for me to do except the rehab they told me to do, there was literally nothing else.

“I was so fatigued, and I still have to manage that, I did whatever rehab I could possibly do. Eat, go to the toilet, that was it. There was no TVs, nobody to talk to. When they first told me, it was the surgeon and one of the main nurses. They said they didn’t know if I’d fully get it all back and that for me was the moment I got upset.

“I cried for maybe two minutes because what happened next was the surgeon said they’d call my parents because I couldn’t speak properly. When he left, the nurse told me I’m young, athletic, the more I do the rehab the more likely I am to get it back'. So, it was like, ‘oh, like an injury’, so that’s what it became in my head, ‘do the rehab and it gets better’, so that became quite simple for me.”

Goddard’s situation though was at first bleak, with no guarantee of a full recovery, as she continues when discussing the breakdown she was given and where her arms, legs and face ranked on the hospital’s 1-5 scale.

“My leg was a one or two out of five, my face was a one out of five, my arm was a zero, completely dead to the world, nothing. I got moved from HDU to the normal ward and that’s when the physio started.

“It started nice and slow, pick a penny up, and I’m struggling! My arm was so heavy, it was doing nothing, but she wanted me to visualise doing it. I thought, ‘this woman is crazy’, but the whole point was to build new pathways in my brain. Where they’d gone in was all bruised, so I had to make a new pathway for signals to go from my brain.

“I had to learn to walk, talk, use a knife and fork, and play football again. I did recover quite quick compared to most. My arm took the longest, I had to do thousands of repetitions. I messaged Lyla and said I wanted to play football again, that was three or four days after it happened - and I’m still bed bound! But that was my whole focus. I did the rehab as much as I could, thousands of every movement you could think of, passing, touch, movement, more power, until it started to feel a bit more normal again.

“The physio who came to my house was like, ‘when you’re ready you can train’ and I was like, ‘what?!’ because this was very early. My leg was working better, but my arm wasn’t. If I fell over, I would face-plant! I wasn’t in any pain, the worst that would happen is I’d fall over!

“I contacted Sian [Osmond] at London Bees who I’d known a long time and she let me train with them. I’ll never forget the first session; it was so funny. The first thing you do is side steps and skips and I’d not learned that. I was like, ‘crap, I didn’t learn this!’. But yeah, I kept going, kept learning, practicing.

“They wanted to sign me four or five months after it happened, but I asked them to wait for two reasons. One, though I could do the stuff, I wasn’t massively comfortable or confident, it was a different sensation. Two, my target was six months, so I had time to get confident, I didn’t want to be just a commodity, I wanted to get as close as I could to being good again. They were patient with me, we worked hard, and I was back playing for Bees.”

Incredibly, six months after suffering her stroke, Goddard was back playing for the club she’d began to make a name for herself as a promising youngster breaking through in the old FA Women’s Super League 2.

Goddard was part of a formidable Arsenal youth team and as a child won the well-remembered Wayne Rooney’s Street Striker.

Also established in the England youth teams, all that is long behind her, but the 33-year-old is in no doubt having the target to aim at of returning to the football pitch was critical in her ability to make as close to a full recovery as possible.

“Definitely, 100%. When I was in the hospital there was an Australian lady, a hard nut, she was going around pushing everyone, and by the end of the week was a bit emotional as I was checking out. She said, ‘I’ve never once had to tell you to do something’.

“Usually when something so traumatic happens it takes so long to accept, the norm is very understandably to be really down, but for me the first year was the most important in the rehab, and a lot of people because it takes so long to process spend a lot of time being down about it, and for me I couldn’t afford that with what I wanted.

“The nurse who told me it was like injury changed everything for me. I was attached to so many machines, but as soon as she said that it gave me a target. I do think that was a huge part of it, if I’d not had that I’d have probably been like everybody else, but I’m also very lucky and don’t take it for granted because when I talk about my story, people contact me with stories that resonate.

“I don’t know anyone who has had all three, but most have had one part at least. Can I talk to them? I always make clear my body responded the way it did through luck and I’m so grateful for that, but I put the work in, but I could have done it all and my body didn’t respond, it’s not a one size fits all.

“When I tell the story, I know it comes across as positive, but I know I’m lucky because it could have been different, and I try and make that clear. I got the physio to take pictures of where I was on day one and every bit of progress, even if it was just my finger moving a little bit more, up to when it plateaued and it was frustrating, I can still look back to where I was and appreciate how far I’ve come, that’s one of the best things I ever did. The truth is it got harder mentality a year or two later when I realised I’d gone as far as I could, it was as good as it was going to get, I wasn’t going to play in the Championship again.

“I can see what I want to do, but I can’t do it, even though I’m very grateful for where I have got to.”

Her face came back the quickest and was back to normal she says in around a week, but had to partake in intense face physio to stretch the muscles which had gone tight.

She admits she would “over-analyse” how she looked every day. Her speech is almost fine, but she still has a slight mumble, and her leg came back within a few weeks.

“I was starting to do fast walks. I could do it, it just felt so different. The only way I can explain it is imagine one leg feels twice the weight of the other leg, it didn’t feel like my leg, it’s really weird, but the more I did things the less weird.

“My hands took the longest, and if I show you,” she says, holding both hands up, “my right hand, this is far as I can go, but this is my left hand, and it won’t go any quicker. I have all the movement, it’s just slower, the one finger has never made a full recovery, but it’s nice how many people I meet who say they can’t tell anything has ever happened.”

Was there a moment she ever saw the light at the end of the tunnel?

The moment the London Bees coaching staff pulled her to one side and told her they wanted to sign her for the new season is the one which is etched in her memory.

“I got a little bit emotional! I knew I felt good, and I was fitting in well in a good Tier 3 side. That was the moment I was like, ‘I’m good enough to play’ to ‘I want be one of the best’. I knew I was never going to be the same player again, the higher you go its fine margins, and I don’t have the coordination I had or the reaction time.

“Even now, at Wimbledon winning a league, or QPR, I know myself I’m a split-second slower, when someone hits a cross in the box if it starts ping-ponging you don’t want it to fall to me because I can’t react quick enough, whereas before reacting and quick feet was my strong suit.

“Now, I find it hard to dribble, if I don’t see the tackle coming, I can’t move quick enough. I’ve had to be smarter and change my game, read the game better, my thought process has to start before everybody else. I can win headers from a goal kick because I can see it coming, but if it’s something quick, you just have to hope it hits me and goes in!”

Her recovery has been remarkable, and as she says, she won the league with AFC Wimbledon, something which seemed a world away lying in her hospital bed.

Now, she’s ready for a new adventure, having announced a few weeks ago she will leave current club QPR once the season has ended.

What lies ahead is unknown, but her story has led to new opportunities, ones she never even thought about pre-her stroke, and she’s just simply grateful to have the opportunity to live a relatively normal life while still doing what she loves.

“It’s mad, because I do a lot of talks now,” she says. “The things I do now I wouldn’t have done before. I thought to myself, ‘what’s the most difficult thing you can do which needs coordination? Ok, snowboarding!’ I like to try the unexpected and in a lot of ways my life is better, it made me focus on my career a lot and I’m earning a lot more than I ever did as a footballer.

“I try to use what happened to spread awareness, motivate, and inspire people as much as I possibly can. I’ve always been the person who is grateful anyway, for the hard work it took, the resilience, the people around me and how much my family did for me, they were unbelievable. I couldn’t even bath myself or wash my hair, my mum did it. I had to go back home, I couldn’t drive, I lost everything and had to start again.

“So now I do things I enjoy. I’m not scared to start over, I’m just grateful and enjoying life…I just think, where I came from to where I am, it does change you, it’s so cliched, but for me it was how could something be so wrong when I was an athlete? I played for Arsenal, England youth teams, in the USA, Denmark, how could something so wrong be in my brain?

“If that aneurysm had burst, I was told it would be life changing disability or fatal, so I’m very lucky. Now it's about dealing with the AVM because more aneurysms can form. I’ve had gamma knife radiation, that will take four or five years to work, they need to close it off 100% and top it off. The embolization was only 65% and it needs to be 90%. I’ll always need more treatment, but if we go over, I’m at risk of losing my left side again.

It’s very fine margins, the whole thing has been mad. I tried to join forums and I couldn’t find anyone who had all three things and I think it’s why my story took off a bit and I was on the news and now doing a lot of talks, because there’s nothing to compare it to.

“The side effects of my treatment were a bit mad; I could be in a match and my left leg would go numb, I’m running on the pitch and can only feel my right side, then it will come back. I had intense pins and needles to the point of pain, but it becomes part of the routine. I’d go down, the physio would come on, stretch my legs and by the time I’d walk off it would be fine, and I was like, ‘what the hell is going on?!’ Because of the bruising in my brain, we would react different because we have different brains, so a lot was happening they had no answer for, I had to sort of just manage.

“I wear a medical bracelet when playing football just in case something happens, they need to know what’s happened because by the time they figure it out I could already be dead. When I join different teams they know my story, I go and do a medical and I’m like, ‘I have a big thing to talk about’ and they’re like, ‘ACL?’ and I’m like, ‘nope…’. I think I’ve given a few medical staff a few heart attacks!”

It does somewhat beg the question; was the injury she suffered all the way back at the start of this story inadvertently the best thing that ever happened to her?

“Yeah, 100%, luckiest thing. I’m so grateful, it does change your outlook. I’ve always been quite calm as a person, so when I see people stressing over the small stuff, I’m like, ‘you’ll be ok, it’s not the end of the world’.

What a story! Thanks for sharing.